Critic Text by CAROLINA LIO

2015

Art is the affirmation of the values of this world. It’s action, as it does not allow to the question going around in circles. It isn’t an answer – there is no answer to the questions that do not define their limits – and yet the art comes as a way to meet the needs of durability. Art imitates life, accompanies it and, reversing it like a glove, gives it a valid boundary. It’s the very act of thinking, which under the eye and the hand turns into an object of greater need. It’s consciousness on the level in which to live and to act are living words of a present continuous overcoming.

Tristan Tzara

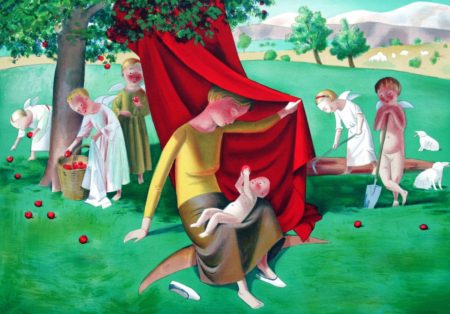

There is an entire front of contemporary art for which the pictorial accuracy is considered a surplus or even a negative connotation that takes away strenght from the most impulsive intention behind the work, and that might obscure it. In a certain sense it is a new way of doing naive painting and, as far as some of these artists would not indentify themselves in this word, mine is a positive note due to their wild instinct and the sincere genuineness that may not belong to all those who make too many virtuosities, who are too technical. They could seem pop artists and are indicated in this line quite often. They accept it. Anyway, in my opinion it’s reductive to relate the sense of an elementary painting, which focuses volumes and wants to be immediate, to the dynamics of the mass consumption, as it had been for Andy Warhol. These artists, indeed, do not want to chase the speed of our times and of our consumptions, rather the opposite: they aim to find into a simple simbolism and a basic iconography a return within the human essence to sensitive and authentic sensations, not sophisticated and therefore pure. I am referring to the English Gary Hume, for example, to the ironic George Condo, to the Marcel Dzama’s works made by ink and watercolor, to the spontaneous portraits of Alice Neel. But in particular it comes to my mind the Czechoslovakian Jan Knap, the theologian-artist who re-proposed in a simplified, childlike key, the sacred art of past centuries to talk about the divine part within every man. And then Donald Baechler, who uses in an extemporaneous, primitive, subversive and anti-rhetoric way the images of a large personal archive.

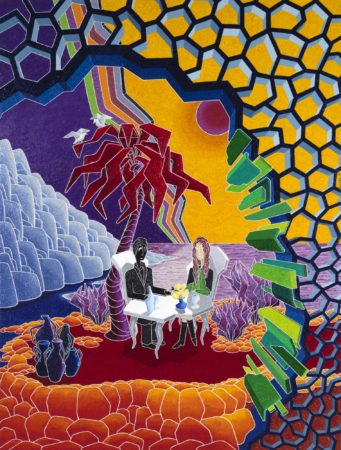

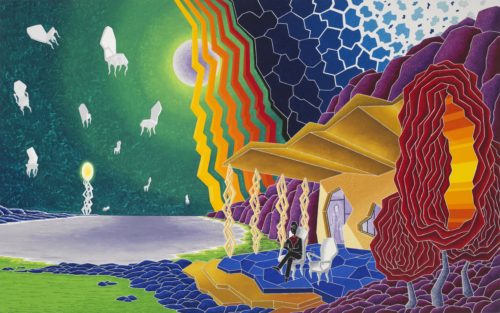

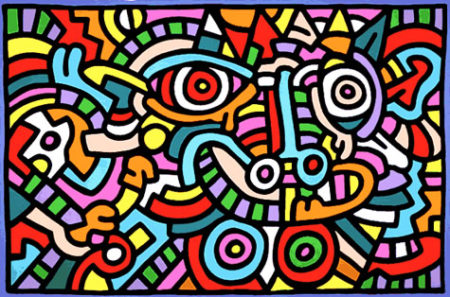

In Francesco Visalli’s pictorial works, instead there is a simplicity composed, neat yet fragmented. Figures are defined as the encounter and the matching of small pieces of color, each of which maintains its own identity. They do not mix with each other almost never and the fragments live in their own colors shades in an independence proudly defended. This is underlined by a barrier of emptiness, a white line that delimits the various perimeters creating on the one hand the separation between the various blocks and, on the other, the glue that holds them together and which elastically forms the whole of the composition.

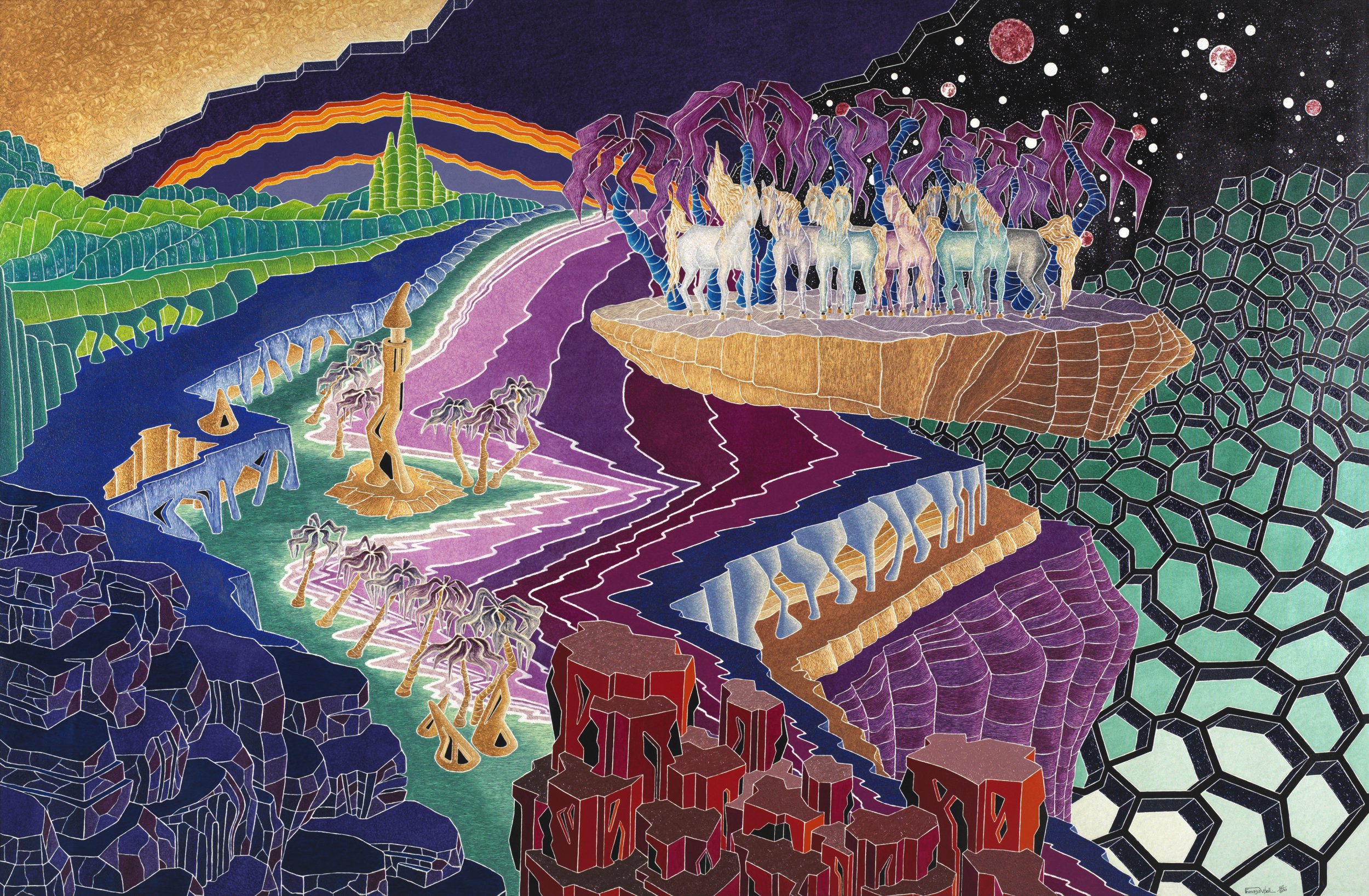

Obviously, the final effect is more similar to a composition rather than to a single representation. It’s like a group on which one need to focus on in order to understand what elements compose more than others the same family, belong to the same subject, underlie a background that imposes itself with the same determination of the main figures. Everything is full, suffers – or enjoies – a horror vacui avoided with any solution, even by filling the space with a galactic black taken by the deep stellar space.

Like in a mosaic where the tiles can not miss even where the story stops, so in the Visalli’s paintings there is the same principle of a surface that must contain tiles, colors and volumes in its entirety, in a balance that can not afford breaking points and interruptions. The harmony comes from the whole combination and perspective plans are sacrificed as useless. The strength of his paintings is, indeed, not the ability to appear realistic but the definition of a hard, net, geometric, rhythmic, sign which bursts into the eye of the viewer perforating the retina with sharp edges created by the screech of lines in contrast with strong colors.

He wrote, the aforementioned Jan Knapp: “I do not like dirtying colors. Colors are the picture of personality. They are a mystery, are like people who should be respected in their identity”. Also for this artist, therefore, the color should be autonomous and independent, not mixed with others and not simply used to give shape to the figure. It has its own “personality”, so each of the chromatisms used in the painting by him (as well as by other contemporary painters including Visalli himself) has a specific sense, a characterization, carries values, symbols and intrinsic senses which can not be mediated or diluted.

After all, that was the same conclusion reached by Dubuffet, whose most famous works were conceived as agglomerates of irregular shapes outlined by a black line and occupied by only one color at a time (including white). The French artist was a true revolutionary who intended to undermine the passive and institutionalized culture of his time, dismantle the traditional aesthetics, knock down pillars, blow up the academic certainties. And he succeeded. Dubuffet, who declared himself “happy to be a common man,” attempted to overthrow the privileged position defended at that time by artists, and to recover the taste of a primitive sense of art through what is called “Art Brut”. Lorenza Trucchi writes that in this art “it is impossible to distinguish the boundary between reality and imagination, conscious and unconscious, physical and mental.” L’Art Brut is, indeed, inspired by people with mental illness, recovering a basic and wild sense of art where man’s energies come into play without the mediation of a vitiated intellect. His work has then been followed as the basis for a further simplification: the stylization that he made Keith Haring. Haring, as Dubuffet before him and as Visalli today, repudiated the traits of classical painting and the perspective, seen as a mere illusion of depth.

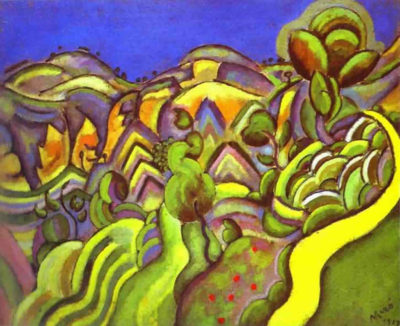

These artists are, indeed, not interested in creating optical illusions. They want to bring back the figure at the level of the canvas, giving dignity to the support they use without having to cover it with geometric systems, fictions and expedients. Moreover even Klee, Matisse and Miro had reduced their figures to silhouettes, extreme in their simplicity, looking for a key to reading that came into conflict with the previous ideas according to which a painting “well done” was supposed to portray the variety of shades, lights, shadows, color, harmonies and contrasts as well as they are present in the true nature.

The fact that these traditional rules were no longer applied, does not mean that artworks have not their balance and harmony. Quite the contrary. Mirò stated that in his paintings “there is a kind of blood circulation. Just a shape shifting, and circulation is blocked, the balance is broken”. While Matisse was rightly convinced that shapes and colors possessed an intrinsic expressive content independent from the any model. Even Picasso, who with the Cubism tried to make three-dimensional painting, never ceased to be also pleased doing graphic works drawn from a line continuous or almost never interrupted.

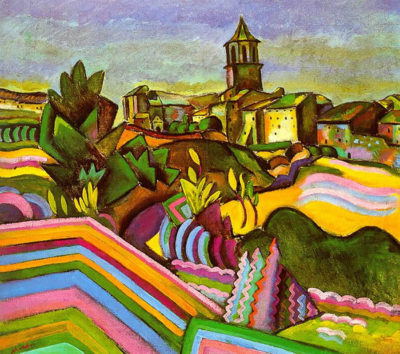

Up to now there has been talk about style and technical choices, but no less importance should be given to the subjects expressed by Francesco Visalli’s painting. Unlike many of the artists mentioned above, indeed, he does not seek the abstraction. Despite he works with geometric shapes, he connects them to describable scenes and recognizable subjects, even if often distorted. We can say that his artworks are surreal paintings because they have no need and requirement of describing something objective, nor in the proportions or in the scenes. The latter are indeed dreamy, spiritual, instinctual, unconscious, highly symbolic and unroll as stories to read. The artist does not care for the reality in itself and is rather interested in its “negative” side, the inversion, revealing the most intimate hidden part. The sentence of Tristan Tzara used in the opening of this text perfectly fits him: “Art imitates life, accompanies it and reversing it like a glove, gives it a valid boundary.” Actually, his pictures are precisely as a overturned glove, the white lines are the seams of a human and mental fabric that reveal the inner side of things, the one in contact with the skin.

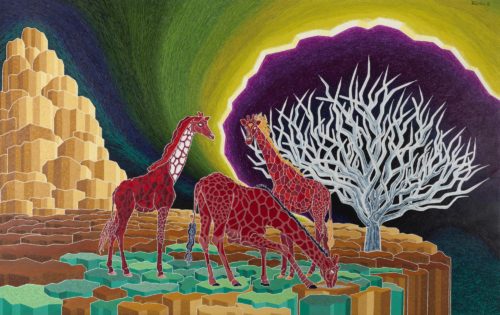

All the surrealist painting, after all, didn’t represent unrealistic scenes to reach mere provocations and paradoxes. On the contrary, it tried to study and represent a deeper reality, more real than reality, a layer beyond the surface. Michele Draguet stated that “the nature that the bourgeois society has failed to completely suffocate, offers us the dream state which gives to our body and our spirit the freedom of which they have an imperative need”. How one can not see in the Francesco Visalli’s works a mutiny against the bourgeois spirit, a subversion of social rules, a poetic and mysterious enigma which at the same time vigorously protests? Halfway between mysticism and science fiction, his scenarios seem romantic and passionate apocalypses. Animals that seem made by metal are moving on withered lands, across bionic vegetations and desolate rocks. Blocks of stones are suspended as if they were cut off from earth because of an explosion. Romantic creatures love and seek each other while they are lost in the fragments of a landscape devastated by laceration.

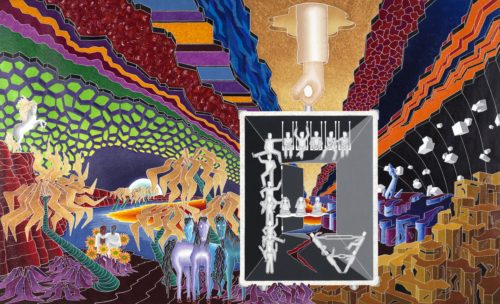

In the title of one of his works all the above notes can be perfectly summed up in “Chaos cosmico”. In this painting a castling of fragments of the world is alternated with a defensive nature and the view of other celestial bodies so close that they suggest a spatial drift and the disruption of any established order.

In another piece, an elongated and shaken, thin and sloppy Madame Quixote (female version of the character of Cervantes) looks toward windmills in the distance. They are without energy and seem to melt down, get lost and being consumed.

Also the figure of “La sposa mancata” has the same features, and it indeed describes a woman waiting for a love that never comes and who, in the meanwhile, is already blocked from thistles that have grown up all around and are addressed to sting her.

Another figure locked in waiting, is “La signora di Avalon”, passionate heroine in red evening dress who, immersed in the ice, romantically resists against her loneliness and gazes at a distant star.

Finally, there is the weakness of the figures of “21 grammi”, title that refers to the weight that is believed to have the soul. In a composition similar to that of a bouquet of screaming flowers, it alludes to violence against women and to the impotent cry of who is forced to endure.

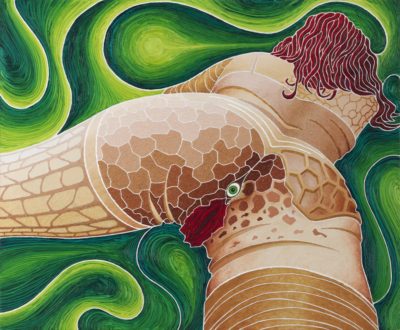

At this point it’s necessary to note that for his own “Autoritratto assente” and in general for the more passionate or even sexually explicit paintings, Visalli uses another technique. His own self-portrait is not a soul that melts in a diaphanous suffering, but it takes corporeality in a fabric of blocks sewn with the usual white line. The effect is like a skin made by splinters, such as a shell, but it is actually a representation of himself for seams, stitches, scars.

The body, marked by an experience behind the other, has become an assemblage of wounds that from one side dismember, on the one hand hold the person together. They tear, arrange, and defend the person through a form of habit at the sound of shots. The pain, the loss, the sense of detachment with the world and a slow sinking of the different parts of the self, find in this case a component which is less sci-fi than other paintings and lower the metaphorical level, not denying the existence of spirituality, but inevitably uniting it to an extreme vulnerability that joins the body.

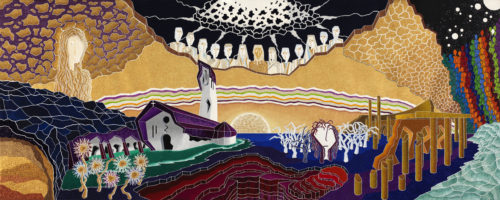

Even in the most spiritual works, for that matter, the metaphor of the divine passes across the expression of a corporeality. It’s the case of the first truly religious painting done so far, “Infinita storia d’amore”. Here, the figure of Christ was obtained by combination of branches surrounding the only one piece of canvas purposely left blank that one could ever found in his works. In the same context, an empty hell goes down across burning stairs, while upward they are opening the seven heavens that lead to a vision of the Paradise inhabited by Christ and his Apostles. The scene is observed by a diaphanous Mary next to a church cracked and crumbling. The work represents not only Visalli’s mystical sense, but mainly a sense of religious crisis, the failure of a moral perfection of the little man who, while inserted into the right band composed by figures representing the twelve tribes of Israel, looks on one side, only colorless character, stranger yet included, rebellious and yet saved.

The sense of salvation despite the disaster, the being fragmented and yet constituted by the union of the pieces, the obsessive fullness from which one can glimpse expanses of universe from which fall into a total emptiness. All these elements are strongly in contrast between them and determine an artist and a personality that defines itself by opposition, by the clash of facets, by the conflict between the parties. An art that does not save shots, first of all to who makes it and tries to give outside, to the viewer, a state of dynamic equilibrium, a peace that flows from a war, a sense of loneliness extrapolated from the crowd.